John Dewey

THEMES ON THIS PAGE:

| 1. EXPERIENCE | 2. PLAYFULNESS VERSUS WORK | 3. MORAL WISDOM | 4. VIRTUES |

John Dewey was an American thinker known for his “pragmatist” approach to philosophy in general, and especially to philosophy of education. He grew up in Vermont, USA, and later received his doctorate at John Hopkins University (Baltimore, Maryland). He taught philosophy at the University of Michigan, University of Chicago, Columbia University, and elsewhere. He published hundreds of articles and dozens of books on a variety of topics – society, education, psychology, art, ethics, journalism, religion, epistemology, logic, science, etc. His approach to society revolves around the values of democracy, freedom, and rational thought. In philosophy of education he developed the so-called progressive (or liberal) education, whose influence on modern education has been considerable. He died at the age of 92.

Dewey was a major pioneer of pragmatism – a philosophical approach that developed in 19th century America, which regards knowledge as a pragmatic tool for dealing with the world (as opposed to an abstract representation of reality).

|

TOPIC 1: EXPERIENCE |

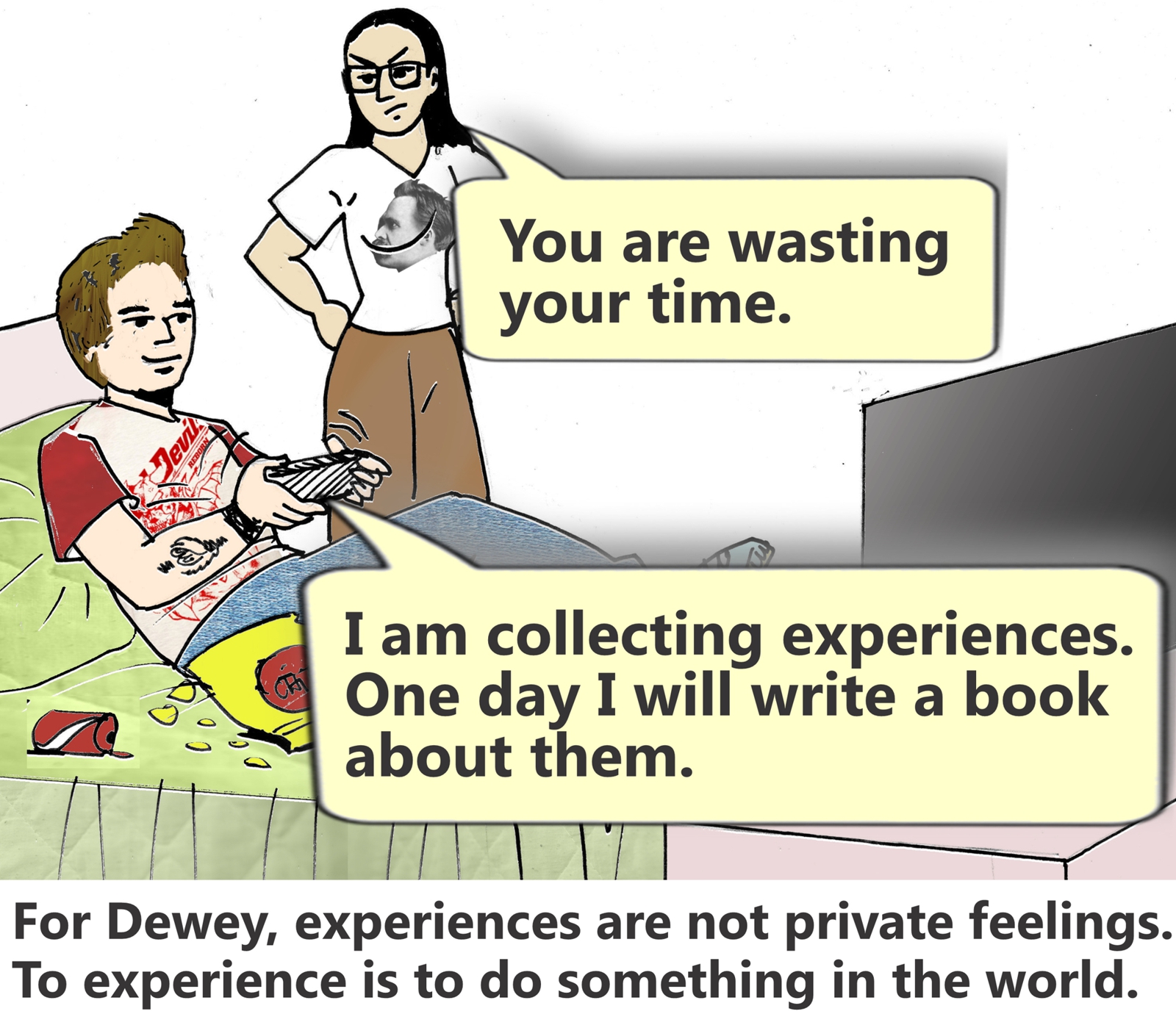

“Experience” is one of the important concepts in Dewey’s philosophy. For him, the meaning of experiences had been distorted in modern philosophy, and this resulted in philosophical confusions. Modern philosophers regarded experience as a private display “inside” the individual’s mind. This created the opposition between an “inner” world of private experiences versus an “external” world of physical objects. The result was epistemological and metaphysical complications without solution, such as: how do we know that the “external” world exists?

To counter these confusions, Dewey argues that experience is not inside our mind but in the world. To experience is to DO something. Experiencing is an event in the natural world just like working or measuring or building. Dewey demonstrates this with the example of science: When scientists make observations, they see – or experience – various results: the position of the moon, the shape of a tree, the needle on a scientific instrument. These experiences are not private feelings in the mind – they involve exploration, manipulation, measurement, thinking, predictions, action, etc.

Dewey, who had a special interest in philosophy of education, applied this to the field of education: Learning abstract ideas is not meaningful to the child unless the learning involves practical activity. Dewey also applied these ideas to aesthetics and ethics: Aesthetic and ethical experiences must be understood as part of an activity, not as “pure” feelings inside the mind.

Dewey, who had a special interest in philosophy of education, applied this to the field of education: Learning abstract ideas is not meaningful to the child unless the learning involves practical activity. Dewey also applied these ideas to aesthetics and ethics: Aesthetic and ethical experiences must be understood as part of an activity, not as “pure” feelings inside the mind.

The following text is adapted (some sentences simplified) from Dewey’s book Democracy and Education (1916).

From Chapter 11: Experience and Thinking

Section 1

The nature of experience can be understood only by noting that it includes an active and a passive element combined in a peculiar way. On the active side, experience is TRYING – this meaning is explicit in the related term “experiment.” On the passive side, it is UNDERGOING. When we experience something, we act upon it, we do something with it; then we undergo the consequences. We do something to the thing, and then it does something to us in return: This is the peculiar combination.

The connection between these two phases of experience indicates how fruitful or valuable the experience is. Mere activity does not make experience. It is scattered, centrifugal, lost. Experience as “trying” involves a change, but a change is meaningless unless it is consciously connected with the return wave of consequences which flow from it. When an activity is continued into the “undergoing” of consequences, when the change made by the action is reflected back into a change made in us, the mere flux is loaded with significance. We learn something. It is not experience when a child merely sticks his finger into a flame; it is experience when the movement is connected with the pain which he undergoes in consequence. From now on, the sticking of the finger into a flame means a burn. Being burned is a mere physical change, like the burning of a stick of wood, if it is not perceived as a consequence of some other action.

[…] To "learn from experience" is to make a backward and forward connection between what we do to things, and what we enjoy or suffer from things in consequence. Under such conditions, doing becomes a trying, an experiment with the world to find out what it is like. The undergoing becomes instruction – discovery of the connection of things.

Section 2

Thought or reflection is the discernment of the relation between what we try to do and what happens in consequence. No experience can have a meaning without some element of thought.

[…] Thinking, in other words, is the intentional attempt to discover specific connections between something which we do and the consequences which result, so that the two become continuous. This cancels their isolation, and consequently their purely arbitrary connection. A unified developing situation takes its place. The event is now understood; it is explained. As we say, it is reasonable that the thing should happen as it does.

Thinking is thus equivalent to making explicit the intelligent element in our experience. It makes it possible to act with a goal in view. It is the condition of our having aims. As soon as an infant begins to expect, he begins to use something which is now happening as a sign of something to follow. He is judging, in however simple a fashion. Because he takes one thing as evidence of something else, and so he recognizes a relationship. Any future development, however elaborate it may be, is only an extending and a refining of this simple act of inference. All that the wisest man can do is to observe what is happening more widely and more minutely, and then select more carefully from what he notes those factors which point to something to happen.

From Chapter 16

It is the nature of an experience to have implications which go far beyond what is at first consciously noted in it. Making conscious these connections or implications enhances the meaning of the experience. Any experience, however trivial in its first appearance, can assume an indefinite richness of significance by extending its range of perceived connections. Normal communication with others is the most suitable way of achieving this development, because it connects the results of the experience of the group, and even the culture, with the immediate experience of an individual. By “normal communication” is meant where there is a joint interest, a common interest, so that one is eager to give, and the other is eager to take.

|

TOPIC 2: PLAYFULNESS VERSUS WORK |

Dewey wrote dozens of books and essays on a variety of topics, but he often connected them to the field of education. A good example is his book How we think (1910). Although the book discusses thinking in general, it pays a special attention to thinking in children, and how thinking can be developed in the educational system. In accordance with his Pragmatist approach to philosophy, Dewey views thinking as essentially connected to activity in concrete situations. Thinking is not idle ideas in the mind, but always oriented towards action – towards dealing with specific situations and challenges in the world.

Dewey wrote dozens of books and essays on a variety of topics, but he often connected them to the field of education. A good example is his book How we think (1910). Although the book discusses thinking in general, it pays a special attention to thinking in children, and how thinking can be developed in the educational system. In accordance with his Pragmatist approach to philosophy, Dewey views thinking as essentially connected to activity in concrete situations. Thinking is not idle ideas in the mind, but always oriented towards action – towards dealing with specific situations and challenges in the world.

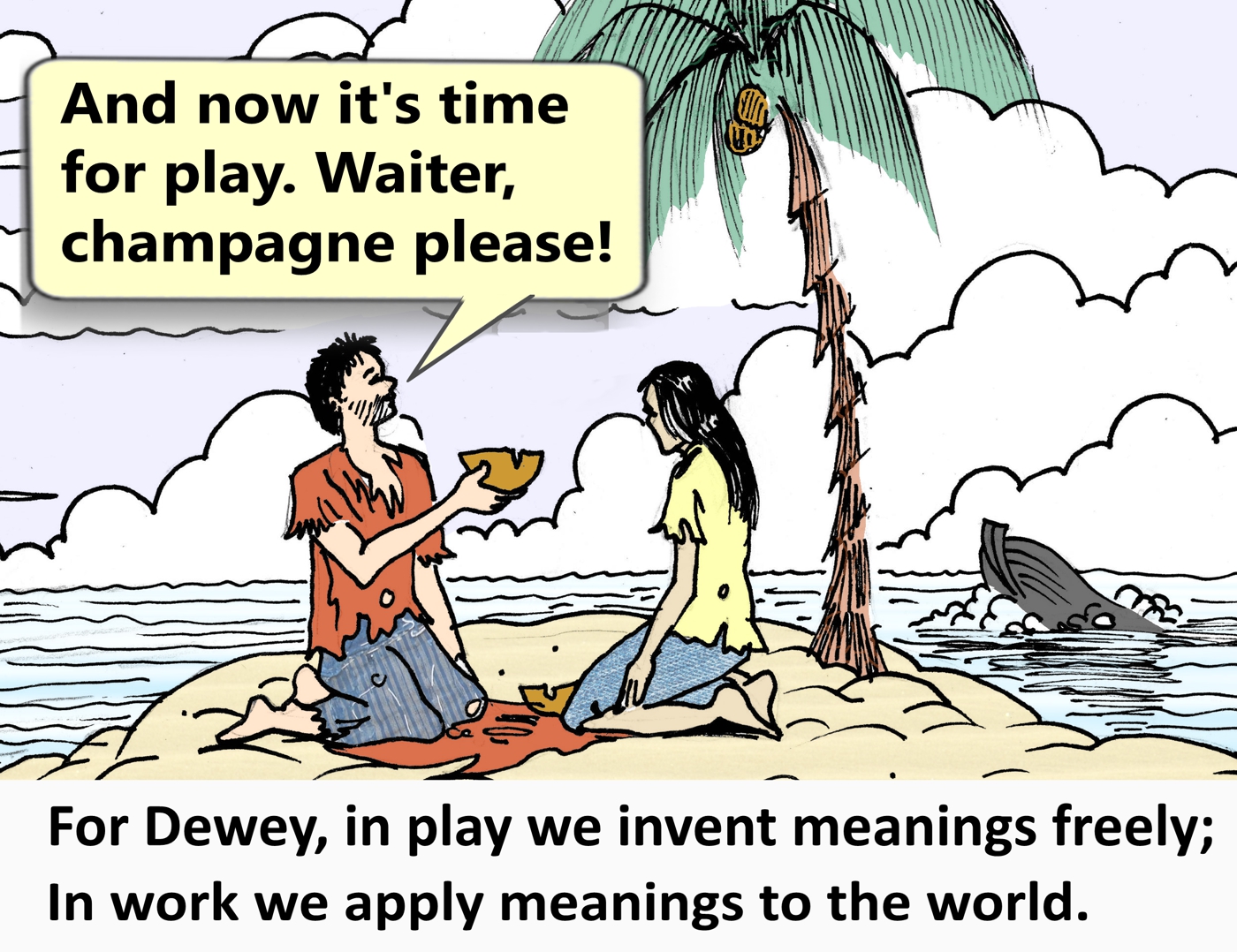

The following text (occasionally simplified for ease of reading) is from the book’s Part 3, “The Training of Thought,” Chapters 12 and 16. The text discusses the difference between two attitudes: the attitude of playfulness and the attitude of work. In playfulness we are free to invent meanings – for example, we regard a broom-stick as a horse, or we pretend that a doll is a real baby. In contrast, in work we apply meanings to real situations. Thus, while in play we enjoy the activity itself, in work we are interested in the result of the activity. Nevertheless, Dewey argues that these two attitudes do not contradict, but can be – and should be – combined. Work without playfulness is boring and oppressive; play that does not aim at producing a product is arbitrary and meaningless.

From Chapter 12: Activity and the Training of Thought

The playful attitude

Playfulness is more important than play. The former is an attitude of mind; the latter is an external manifestation of this attitude. When we treat things simply as vehicles of imagination, what is imagined dominates the thing. Hence, the playful attitude is an attitude of freedom. The person is not limited by the physical characteristics of things, nor does he care whether a thing really means what he takes it to represent. When the child plays horse with a broom, and train cars with chairs, it does not matter that the broom does not really represent a horse, or a chair a locomotive. In order that playfulness would not become arbitrary fancy, and would not terminate in an imaginary world outside the world of actual things, it is necessary that the play attitude would gradually pass into a work attitude.

The work attitude is interested in means and ends

What is work – work not as mere external performance, but as attitude of mind? Work signifies that the person is no longer content to accept the meanings that things suggest, and to act according to them, but he demands agreement between meaning and the things themselves. In the natural process of growth, children start regarding as inadequate irresponsible plays of make-believe. A fiction gives content in a way that is too easy. There is not enough stimulus to produce satisfactory mental activity. When the child reaches this point, he must apply the ideas that things suggest to the things, with some regard to how well they fit them.

A small cart, resembling a "real" cart, with "real" wheels and body, satisfies the mental demand better than merely pretending that any arbitrary thing is a cart. Occasionally, it is more rewarding to set a "real" table with "real" dishes than to pretend that a flat stone is a table and that leaves are dishes. The child’s interest may still center on the meanings, and the physical things may be important only as amplifying a certain meaning.

So far, the attitude is one of play. But now the meaning must find appropriate embodiment in actual things. The dictionary does not permit us to call such activities “work.” Nevertheless, they represent a genuine passage of play into work. Because work (as a mental attitude, not as mere external performance) means interest in the adequate embodiment of a meaning (a suggestion, purpose, aim) in objective form, through the use of appropriate materials and appliances. Such an attitude involves meanings created in free play, but it controls their development by making sure that they are applied to things in ways that are consistent with the observable structure of the things themselves.

[…]

The point of this distinction between play and work may be clarified by comparing it with a more usual way of explaining the difference. In play activity, it is said, the interest is in the activity for its own sake; in work, the interest is in the product, or result, in which the activity terminates. Hence, the former is purely free, while the latter is constrained by the goal to be achieved.

When the difference is stated in this sharp way, it almost always introduces a false, unnatural separation between process and product, between activity and its achieved outcome. The true distinction is not between an interest in activity for its own sake and interest in the external result of that activity, but rather between an interest in an activity just as it flows from moment to moment, and an interest in an activity as leading to an outcome, and therefore as possessing a thread of continuity that connects together its successive stages. Both may equally involve interest in an activity "for its own sake"; but in one case, the activity is more or less casual, following the coincidence of the circumstances and whim, or of dictation. In the other case, the activity is enriched by the sense that it leads somewhere, that it amounts to something.

From CHAPTER 16: Some General Conclusions

[…] In play, interest centers on activity, without much reference to its outcome. The sequence of acts, images, emotions, is enough in itself. In work, the goal holds attention and controls the attention given to means. Since this is a difference in the focus of interest, the contrast is a matter of emphasis, not of sharp division.

[…] Exclusive interest only in the result changes the work to drudgery. […] Whenever a piece of work becomes drudgery, the process of doing loses all value for the doer. He cares solely for what he will have at the end of it. The work itself, the spending of energy, is hateful. It is just a necessary evil, since without it some important end would be missed. […] To be playful and serious at the same time is possible, and it defines the ideal mental condition. […] Mental play is open-mindedness, faith in the power of thought to preserve its own integrity without external supports and arbitrary restrictions. Hence, free mental play involves seriousness, earnestly following the development of the subject-matter.

|

TOPIC 3: MORAL WISDOM |

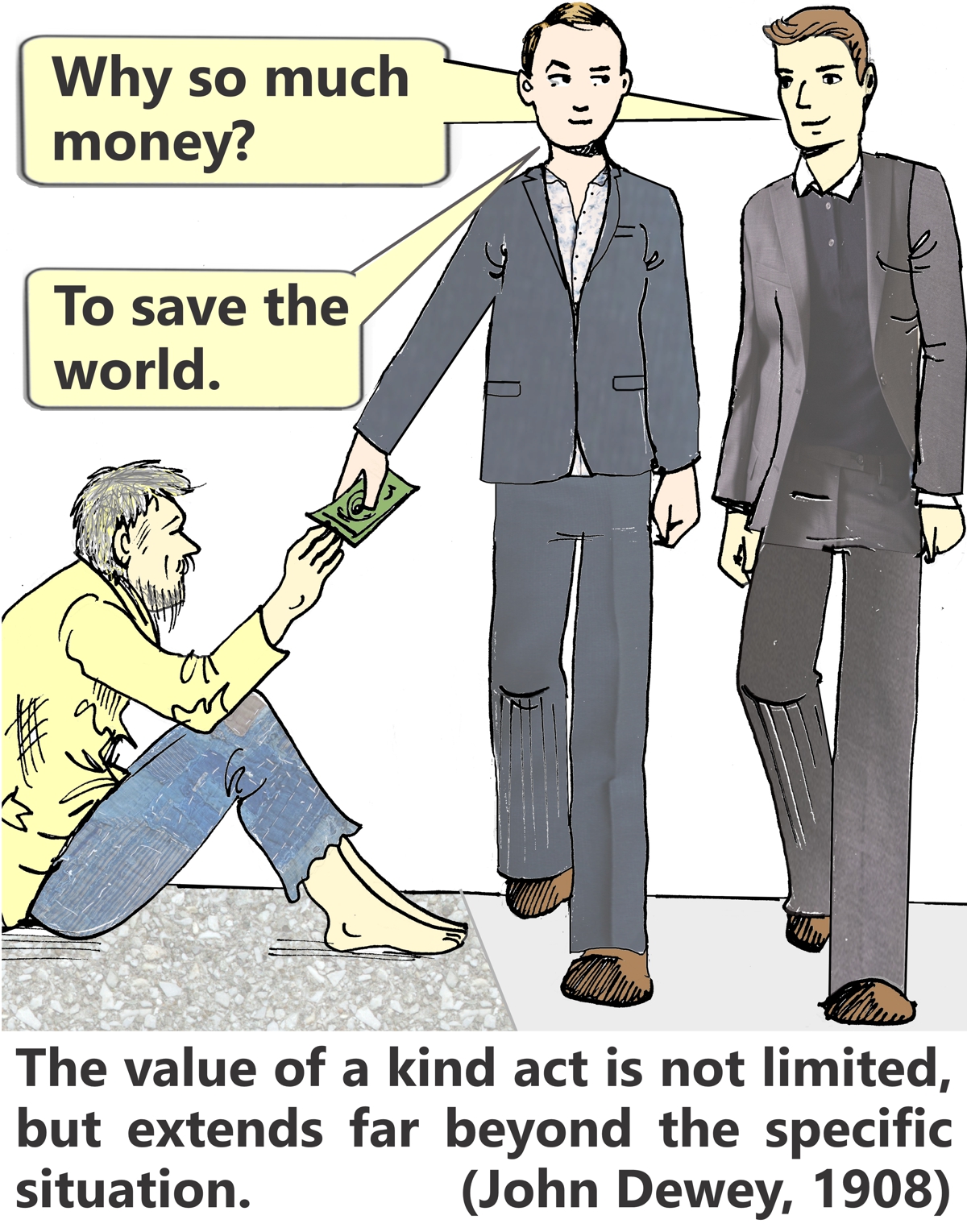

Dewey devoted several essays and books to ethics and society. Faithful to his “pragmatist” approach, he regarded ethical ideals not as something fixed and abstract, but as part of real life. Ethical values always relate to the specific situations in our life, to specific behaviors and dilemmas. But this does not mean that ethical values are “small” things. If we act morally in specific situations, we thereby promote the wider horizon of the good.

Dewey devoted several essays and books to ethics and society. Faithful to his “pragmatist” approach, he regarded ethical ideals not as something fixed and abstract, but as part of real life. Ethical values always relate to the specific situations in our life, to specific behaviors and dilemmas. But this does not mean that ethical values are “small” things. If we act morally in specific situations, we thereby promote the wider horizon of the good.

The following text is adapted from Dewey’s book Ethics (1908), Chapter 19, section 4. (Some sentences modified for ease of reading.)

THOUGHTFULNESS: While the center of moral wisdom must involve immediate, unreflective responsiveness to good and bad, the personality behind these intuitive understandings must be thoughtful and serious-minded. There is no individual, however morally sensitive, who can do without cool and calm reflection, or whose intuitive judgments (if reliable) are not largely the result of prior thinking. Every voluntary act is intelligent. In other words, it includes an idea of the end to be reached, or the expected consequences. […]

As one’s habit of reflecting grows, one becomes aware that the values of one’s particular ends are not limited, but extend far beyond the specific situation in question. They extend so far, indeed, that their range of influence cannot be predicted or defined. A kind act may have not only the particular consequence of relieving somebody’s present suffering, but may also make a difference to his entire life, or it may give a radically different orientation to the giver’s interest and attention.

These larger and remoter values in any moral act transcend the end which was in the doer’s conscious awareness. The person must always aim at something definite, but as he becomes aware of this atmosphere of far-reaching ulterior values, the meaning of his special act is thereby deepened and widened. An act seems temporary and circumstantial, but its meaning is permanent and wide. The act passes away, but its significance remains in the additional meaning that may continue to grow. To live in the recognition of this deeper meaning of acts is to live in the ideal, in the only sense in which it is useful for a person to dwell in the “ideal.”

Our "ideals” – our types of excellence – are the various ways in which we envision the always-expanding values of our concrete acts. Every achievement of good deepens and quickens our sense of the inexhaustible value that is contained in every right act. With achievement, our conception of the possible goods of life increases, and we find ourselves called to live on a deeper and more thoughtful level.

An ideal is not some remote and all-inclusive goal, a fixed “highest good” for which other things serve as means. It is not something that is in contrast with the direct, local, and concrete quality of our actual situations, and it does not make these situations insignificant. On the contrary, an ideal is the conviction that each of these special situations carries with it a final value, a meaning which in itself is unique and inexhaustible. To erect "ideals" of perfection which are different from the serious recognition of the possible development that exists in each concrete situation, is in the end to pay with sentimentalities, if not with mere words. And meanwhile, it is to direct thought and energy away from the situations which need – and which welcome – the perfecting care of attention and love.

|

Philosophers

-

- Philosopher

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.